Anything demonstrated in this post should come with a public health warning – these options are explored for reference only, and modifying them without being able to observe and reason about their effects should be avoided.

You have been warned.

The two compilers

The JVM that ships with OpenJDK contains two compiler back-ends:

- C1, also known as ‘client’

- C2, also known as ‘server’

The C1 compiler has a number of different modes, and will alter its response to a compilation request given a number of system factors, including, but not limited to, the current workload of the C1 & C2 compiler thread pool.

Given these different modes, the JDK refers to different tiers, which can be broken down as follows:

- Tier1 – client compiler with no profiling information

- Tier2 – client compiler with basic counters

- Tier3 – client compiler with profiling information

- Tier4 – server compiler

From this point on, when referring to the C1 compiler, I’m talking about Tier3.

Thresholds

At a very high level, the JVM bytecode interpreter uses method invocation and loop back-edge counting in order to decide when a method should be compiled.

Since it would be wasteful and expensive to compile methods that are only ever called a small number of times, the interpreter will wait until a method invocation count is over a particular threshold before it is compiled.

Thresholds for various levels of compilation can be modified using flags passed to the JVM on the command line.

The first such threshold that is likely to be triggered is the C1 Compilation Threshold.

Flags side-note

To view all the available flags that can be passed to the jvm, run the following command:

java -XX:+PrintFlagsFinal

Running this on my local install of JDK 1.8.0_60-b27 shows that there are 772 flags available:

[pricem@metal ~]$ java -XX:+PrintFlagsFinal 2>&1 | wc -l

772For the truly intrepid, there are even more tunables available if we unlock diagnostic options (more on this later):

[pricem@metal ~]$ java -XX:+UnlockDiagnosticVMOptions -XX:+PrintFlagsFinal 2>&1 | wc -l

873Example code

Code samples from this post are available on github.

Clone the repository, then build with:

./gradlew clean jar

C1 Compilation Invocation Threshold

The first trigger that a method is likely to hit is for C1 compilation threshold. This threshold is specified by the flag:

[pricem@metal ~]$ java -XX:+PrintFlagsFinal 2>&1 | grep Tier3InvocationThreshold

intx Tier3InvocationThreshold = 200This setting informs the interpreter that it should emit a compile task to the C1 compiler when an interpreted method is executed 200 times.

Observing this should be simple – all we need to do is write a method, call it 200 times and watch the compiler doing its work.

Enabling logging of compiler operation is a simple matter of supplying another JVM argument on start-up:

-XX:+PrintCompilation

Without further ado, let us try to observe our method being compiled after 200 invocations. The script being called will log any statements from the program, and also any other output to stdout that is relevant to compilations for this project.

We would expect to see a message saying that the exerciseTier3InvocationThreshold method is compiled.

[pricem@metal jvm-warmup-talk]$ bash ./scripts/c1-invocation-threshold.sh

LOG: Loop count is: 200No compilation message. I’ll shortcut a bit of investigation here and point out that the Tier3 compile threshold seems to work on boundaries of power-two numbers:

[pricem@metal jvm-warmup-talk]$ bash ./scripts/c1-invocation-threshold.sh 255

LOG: Loop count is: 255Still no compilation; let’s perform one more invocation…

[pricem@metal jvm-warmup-talk]$ bash ./scripts/c1-invocation-threshold.sh 256

LOG: Loop count is: 256

132 47 3 com.epickrram.t.w.e.t.C1InvocationThresholdMain::exerciseTier3InvocationThreshold (6 bytes)Finally our method is compiled. This pattern is repeated for larger numbers of invocation threshold:

[pricem@metal jvm-warmup-talk]$ java -cp build/libs/jvm-warmup-talk-0.0.1.jar -XX:+PrintCompilation

-XX:Tier3InvocationThreshold=1000 com.epickrram.t.w.e.t.C1InvocationThresholdMain 1023 | grep -E "(LOG|epickrram)"

LOG: Loop count is: 1023No compilation at 1023 invocations.

[pricem@metal jvm-warmup-talk]$ java -cp build/libs/jvm-warmup-talk-0.0.1.jar -XX:+PrintCompilation

-XX:Tier3InvocationThreshold=1000 com.epickrram.t.w.e.t.C1InvocationThresholdMain 1024 | grep -E "(LOG|epickrram)"

LOG: Loop count is: 1024

128 18 3 com.epickrram.t.w.e.t.C1InvocationThresholdMain::exerciseTier3InvocationThreshold (6 bytes)1024 invocations triggers compilation.

C1 Loop Back-edge Threshold

As mentioned earlier, the JVM bytecode interpreter will also monitor loop counts within a method. This mechanism allows the runtime to spot that a method is hot despite it not being invoked many times.

For example, if we have a method that contains a loop executing many thousands of times, we would want that method to be compiled, even if it was only invoked relatively infrequently.

The relevant flag for this setting is:

Tier3BackEdgeThreshold

[pricem@metal jvm-warmup-talk]$ java -XX:+PrintFlagsFinal 2>&1 | grep Tier3BackEdgeThreshold

intx Tier3BackEdgeThreshold = 60000Using another example program, we can observe the interpreter emitting a compile task once the loop count within a method reaches the specified threshold:

[pricem@metal jvm-warmup-talk]$ bash scripts/c1-loop-backedge-threshold.sh 60416

LOG: Loop count is: 60416

137 48 % 3 com.epickrram.t.w.e.t.C1LoopBackedgeThresholdMain::exerciseTier3LoopBackedgeThreshold @ 5 (25 bytes)Once again, there seems to be a slight difference in the required number of loop iterations and the specified threshold. In this case, we need to execute the loop 60416 times in order for the interpreter to recognise this method as hot. 60416 just happens to be 1024 * 59, it’s almost as though there’s a pattern here…

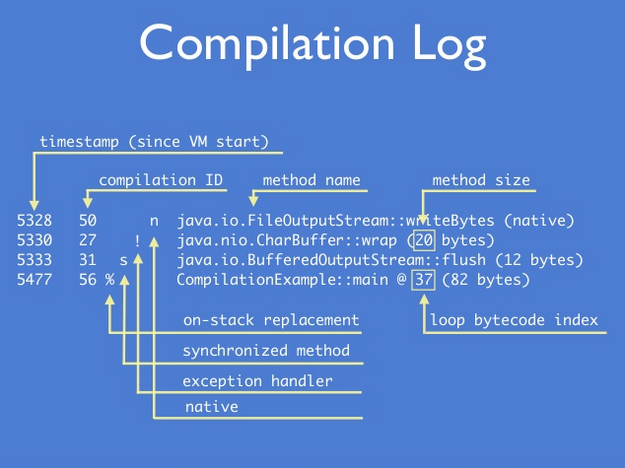

PrintCompilation format

In order to understand what is happening here, we need to take a brief foray into understanding the output from the PrintCompilation command. Rather than draw my own fancy graphic, I’m going to reference a slide from Doug Hawkins’ excellent talk JVM Mechanics.

Using this reference, we can break down the information in the log output from our test program:

137 48 % 3 com.epickrram.t.w.e.t.C1LoopBackedgeThresholdMain::exerciseTier3LoopBackedgeThreshold @ 5 (25 bytes)- This compile happened 137 milliseconds after JVM startup

- Compilation ID was 48

- This was an on-stack replacement (more on this later)

- This compilation happened at Tier3 (C1 profile-guided)

- The OSR loop bytecode index is 5

- The compiled method was 25 bytecodes

Verifying the detail

Let’s go and take a quick look at what these bytecode references are. If we decompile the method using javap:

[pricem@metal jvm-warmup-talk]$ javap -cp build/libs/jvm-warmup-talk-0.0.1.jar -c -p

com.epickrram.t.w.e.t.C1LoopBackedgeThresholdMainWe can see the disassembled bytecode of the method in question:

private static long exerciseTier3LoopBackedgeThreshold(long, int);

Code:

0: lload_0

1: lstore_3

2: iconst_0

3: istore 5

5: iload 5

7: iload_2

8: if_icmpge 23

11: ldc2_w #22 // long 17l

14: lload_3

15: lmul

16: lstore_3

17: iinc 5, 1

20: goto 5

23: lload_3

24: lreturnThis tells us that the method contains 25 bytecodes, so that explains one number. We can also see the goto instruction at bytecode index 20, and its target bytecode index 5.

Comparing this with the method source:

private static long exerciseTier3LoopBackedgeThreshold(final long input, final int loopCount)

{

long value = input;

for(int i = 0; i < loopCount; i++)

{

value = 17L * value;

}

return value;

}With a little bit of reasoning, we can figure out that bytecode 5 is the point at which we load the loop counter variable i in order to do the comparison to the loopCount parameter.

This bytecode index then, is at the start of the loop, and would be an ideal place to jump to executing the newly compiled method.

On-Stack Replacement

On-Stack replacement is a mechanism that allows the interpreter to take advantage of compiled code, even when it is still executing a loop for that method in interpreted mode.

If we imagine a hypothetical workflow for our JVM to be:

- Start executing a method loopyMethod in the interpreter

- Within loopyMethod, we execute an expensive loop body 1,000,000 times

- The interpreter will see that the loop count has exceeded the Tier3BackedgeThreshold setting

- The interpreter will request compilation of loopyMethod

- The method body is expensive and slow, and we want to start using the compiled version immediately. Without OSR, the interpreter would have to complete the 1,000,000 iterations of slow interpreted code, dispatching to the complied method on the next call to loopyMethod()

- With OSR, the interpreter can dispatch to the compiled frame at the start of the next loop iteration

- Execution will now continue in the compiled method body

C1 Compilation Threshold

There is one other threshold that we need to concern ourselves with, and that is the Tier3CompileThreshold. This particular setting is used to catch a method containing a hot loop, whose back-edge count is not high enough to trigger on-stack replacement due to a high loop back-edge count.

The heuristic for determining whether a method should be compiled, described here, looks something like this:

boolean shouldCompileMethod (invocationCount, backEdgeCount) {

if ( invocationCount > Tier3InvocationThreshold ) {

return true;

}

if ( invocationCount > Tier3MinInvocationThreshold &&

invocationCount + backEdgeCount > Tier3CompileThreshold ) {

return true;

}

return false;

}Given this formula, we should be able to create a scenario for triggering this threshold. In order to exercise the trigger, let’s look at the defaults on my version of java:

intx Tier3CompileThreshold = 2000

intx Tier3InvocationThreshold = 200

intx Tier3MinInvocationThreshold = 100We need to make sure that the method is called fewer than Tier3InvocationThreshold times and greater than Tier3MinInvocationThreshold times, while increasing the back-edge count to greater than Tier3CompileThreshold. On the next invocation of the method, compilation should occur.

So, if we invoke a method 100 times, and it generates a loop back-edge count of 21 per invocation, then we should exceed the Tier3CompileThreshold:

100 + (100 * 21) == 2200 > Tier3CompileThresholdOn the 101st invocation, the interpreter should trigger a compilation.

Of course, given that so far each threshold seems to have had some power-of-two-based wiggle room as far as the interpreter is concerned, this magic formula doesn’t work out exactly. In fact, in this example, the method must be executed 147 times in order for compilation to occur!

Executing this test program yields the following output:

[pricem@metal jvm-warmup-talk]$ bash ./scripts/c1-compilation-threshold.sh

LOG: Loop count is: 21

LOG: Finished invocation: 1, back-edge count should be 21

LOG: Finished invocation: 2, back-edge count should be 42

LOG: Finished invocation: 3, back-edge count should be 63

LOG: Finished invocation: 4, back-edge count should be 84

...

LOG: Finished invocation: 145, back-edge count should be 3045

LOG: Finished invocation: 146, back-edge count should be 3066

LOG: Pausing for a few seconds to make sure compile hasn't been triggered yet...

LOG: About to perform invocation 147

5151 176 3 com.epickrram.t.w.e.t.C1CompilationThresholdMain::exerciseTier3CompilationThreshold (27 bytes)It can be seen that in this scenario, we have not triggered the invocation threshold (i.e. invocation count < 200), nor have we triggered the back-edge threshold. The interpreter has correctly identified the method as being worthy of compilation, so the runtime is able to provide an optimised version for future invocations.

Summary

We have seen that for the C1 compiler when operating in tiered mode, there are 3 flags that control when a method is considered for compilation.

In my next post, I’ll be looking at the corresponding flags for the C2 compiler, and how they are affected by tiered and non-tiered mode.

Follow @epickrram!function(d,s,id){var js,fjs=d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0],p=/^http:/.test(d.location)?’http’:’https’;if(!d.getElementById(id)){js=d.createElement(s);js.id=id;js.src=p+’://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js’;fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js,fjs);}}(document, ‘script’, ‘twitter-wjs’);